Kinesthetic Knife Sharpening

My method for sharpening reed knives does not involve numbers, coins, jigs, or any precise tool for measuring angles. Instead, I suggest a kinesthetic (feel-based) approach. Reed makers will spend the least amount of time sharpening knives if they get used to how the knife feels on the sharpening apparatus (in my case, stones and rods). Relying on sensory feedback is the quickest way to identify which part of the knife is sharp and which part is dull, thus expediting the process to a totally and evenly sharp knife. Sharpening methods that suggest numbered angles or passes do not account for (1) the predetermined angle at which each knife is ground, nor (2) the amount of pressure being applied to each individual pass. We are not robots after all.

This protocol will break down the strategies and equipment I employ when sharpening my reed knives. Everything below is based on my personal preference and nothing has been scientifically proven. I have taken inspiration from my mentors as well as heaps of YouTube videos by commercial reed makers, professional chefs, and Japanese knife makers. This paper can actually serve as a sharpening protocol for any type of knife with a non-serrated edge. Which leads me to my main argument: Reed knives are still just knives. The rake-like edge that makes a knife a “reed knife” should only be visible on a microscopic level and is created at the very last step of the sharpening process.

Sharpening Equipment

Ceramic and Steel. I exclusively use sharpening equipment where only water is needed for lubrication. I know many reed makers that use India and Arkansas stones with honing oil, but it is too messy for me. And I do not want to risk clogging the pores of my reeds with oil. For this reason, I stick to ceramic whetstones, ceramic crock sticks, and sharpening steel rod. (Diamond stones work great and water lubricates them well. However, most stones on the market either take too much effort to "break in," or they wear down too quickly to justify their expensive price.)

As for stones, I go through three levels of fineness to hone the blade:

Level 1: Grinding

If a knife is severely damaged or refuses to sharpen, use a coarse ceramic whetstone to grind a new edge into the blade. I use a Shapton* #320 stone. I rarely grind knives, but if a knife I like is towards the end of its life, I will revive it with this stone.

Level 2: Sharpening

If a knife does not stay sharp with a burnishing rod or fine ceramic stick/stone, I will turn to a medium ceramic whetstone. Several stones are appropriate for this stage, I prefer the Shapton #1000 stone. For most brands of stones, anywhere from 600 to 1500 grit is appropriate. Caution: Grits are not consistent across stone brands. This is why I suggest general levels of stone (coarse, medium, fine, etc.), as that is how most brands advertise their stone for this stage of sharpening.

Level 3: Polishing

Fine or super-fine grit stones will smooth the burr of a knife. on the reed. Again, many stones will work for this level. I use a Shapton #5000 stone.

*I prefer using Shapton stones because they are "splash-and-go" stones, meaning you don't have to soak them before using (again, less messy the better). Also, Shapton makes both ceramic and "glass" stones. I have used both and they both work great. My only observation the ceramic stones give more feedback than the glass, so I slightly prefer them.

Rods

During a reed making session, I will only have a steel burnishing rod and a fine ceramic crock stick on my desk for touching up the knife. The steel works until it doesn't, at which point I will use the ceramic stick. If that no longer retains the edge, I will turn to the stones, working progressively backwards trough the levels until I achieve the desired edge.

I use a Lansky fine ceramic stick, and a Dickoron ultra fine sharpening steel.

Reed Knives

Reed makers are constantly debating over which knife is the best, and I am not interested in contributing to that discussion. For my protocol, you will need 1 beveled knife, and 1 double hollow ground knife. I use beveled knives for scraping the bark off my reeds, and double hollow ground knives for finishing the tip and creating a smooth finish along the entire scrape.

Aside from the knives you can buy from specialty websites, it is very easy to make a double-hollow ground knife yourself: Buy a carbon steel straight edge razor (eBay, AliExpress, Amazon, etc), remove the guide, and attach it to a universal tool handle (I use General and Nicholson brands). This is a cheap and effective way to create a wonderful reed knife.

Kinesthetics

Knife sharpening involves the entire upper body, and although I said we are not robots, we are going to simplify body parts down to singular, mechanical movements. The key to this approach is to always maintain a degree of pressure that is gentle enough to be sensitive to the feedback* given by the sharpening apparatus. Allow the stone to do the sharpening and let it tell you where the knife is dull. The body's job is to just hold the knife in place and apply pressure to the dull parts of the knife until it is evenly sharp. If an angle is held steadily, the stone/rod will give feedback until that part of the edge has been turned over to the other side, at which point the feedback feels smoother, almost as if the knife is cutting the stone. Kinesthetic knife sharpening requires some bravery, as you will be touching the edge of the knife in various places to ensure even sharpness. But trust that I am not suggesting anything that will cause harm, as long as the techniques are done properly.

*It is hard to describe the "feedback" sensation, but you will develop the sensitivity with practice. It similar to the feedback you feel in your hands when filing your finger nails.

Stone Sharpening

When sharpening with a stone, I designate singular roles to each body part on either side of my body:

Dominant Side (holds the handle):

My arm is loosely locked, moving from the hinge of the shoulder blade as guided by my non-dominant side.

My wrist is tightly locked in place.

My fingers are loosely gripping the knife handle. The fingers are where the feedback is felt the most.

Non-Dominant Side (touches the blade):

My arm is sturdy, hinged at the shoulder blade, guiding the knife forward and back in a steady motion. Imagine you are a deli meat slicer cutting thin slices off of the stone.

My wrist is tightly locked in place.

My fingers are applying gentle downward pressure onto the blade, either focused on one part of the blade or spread evenly throughout, depending on step and demands of the blade. I only apply pressure as I push the knife away from me, letting up as it comes back towards me.

Rod Sharpening

I only use rods that I hold in my hand, as opposed to sets of crock sticks that sit in a base. This allows me to feel the feedback through my dominant side as I would when using a stone. Ceramic rods must be handled with as gentle pressure as the stone. Steel rods are slipperier and require slightly more pressure to ensure even contact throughout each pass.

Dominant Side (holds the rod):

My arm is relaxed, gently pressing the rod into the bench surface at an angle. Imagine a cellist putting their end pin into the floor of a nice stage.

My wrist is tightly locked in place.

My fingers are loosely gripping the rod, allowing enough sensitivity to receive feedback.

Non-Dominant Side (holds the knife):

My arm is sturdy, hinged at the shoulder blade, applying gentle pressure to the rod while steadily pulling the blade either from away my body towards the bench surface, or towards my body away from the bench, depending on the side of the knife. The pressure should resemble drawing on paper with a wooden pencil.

My wrist is tightly locked on place.

My fingers are loosely gripping the knife, allowing enough sensitivity to receive feedback.

Feeling the burr

After completing a step that involves creating a strong, rough burr on one side of the blade, take the pad of the thumb and gently slide it down and away off the opposite side of the knife to the one touching the stone during that step. For example, if the back of the knife was touching the stone, slide your thumb down and away from the edge of the front of the knife. The burr will feel like a thin line of coarse sidewalk concrete. The dull parts of the knife will feel smooth in comparison. This is how you tell where to apply pressure when going back to the stone.

Testing for even sharpness

After the knife has been sharpened and/or polished, place the heel of the knife straight down onto your non-dominant thumbnail (perpendicular to the ground) and gently pull it towards you with no pressure. If the knife is sharp, it will stick to your nail like a magnet along the entire blade. If it is not evenly sharp, it will skip off of your nail at the dull points. This is how tell where to apply pressure when going back to the stone/rod.

Testing before scraping

Before scraping the reed, gently scrape the keratin off of your non-dominant thumbnail with no pressure. Test this along the entire blade after testing for even sharpness. If the knife is properly sharp, it will create the same desirable curls that would come off of the cane. The edge should feel quite sticky.

STEP-BY-STEP SHARPENING PROTOCOL

Throughout this section I will refer to the “front” and "back" sides of the knife. The front side of the blade is the side that is facing away from you when holding the knife in your dominant hand. The back side of the blade is facing towards you. With beveled knives, the flat side is the front and the beveled side is the back.

Beveled Knives

Beveled knives are significantly easier to sharpen than double hollow ground knives because the desired angle is built into the blade. This allows you to hold the beveled side flat on the stone creating an edge that is structurally reinforced by the entire blade.

You do not need to lift either edge off of the sharpening apparatus, except when using the rods. If you do, this will create an edge that is only reinforced by the metal touching the stone, requiring the edge to dull quicker and more frequently.

Level 1 (Re-grinding): Put the beveled side of the blade on a coarse stone and make several passes until you can feel a strong, consistent burr along the entire edge of the other side of the knife (see "Feeling the burr"). Do not turn the knife over and sharpen the flat side of the blade

Level 2 (Sharpening): On a medium stone, make several passes on the beveled side of the blade as you did in Level 1 but stop when the knife is evenly sharp (see "Testing for even sharpness")

Level 3 (Polishing): On a fine/super-fine stone, continue to make several passes on the beveled side of the blade. Then flip the knife over and make several passes until you no longer receive feedback from the stone. If you have not yet received a desired edge, you may flip the knife back and forth making few passes on each side or revert back to Level 2. If you were diligent during the entire process, the bevel should look glossy and reflective.

Sharpening Steel: Put the flat side of the blade on the steel at an acute angle and make a few passes toward your body. Use the smallest angle possible that still generates feedback. Then turn the knife over onto the beveled side and make a few passes away from your body. Slowly increase the angle during your passes until you no longer receive feedback. This final step separates the reed knife from any other knife and creates the rake shape at a microscopic level.

Reminder: I only use the ceramic stick during a reed making session, when the steel is not sufficiently honing the edge.

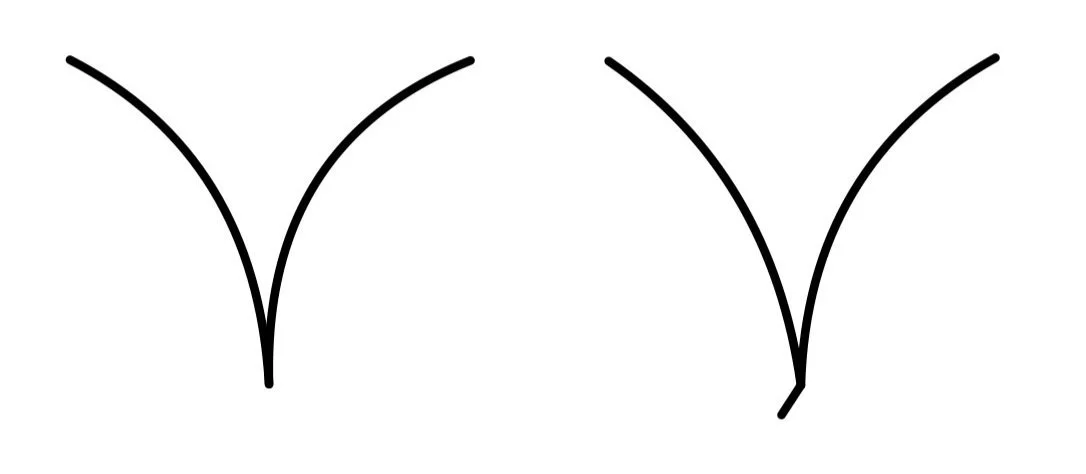

left: regular knife

right: reed knife

Double Hollow Ground Knives

Finding the right angle* for your double hollow ground knife requires trial and error, but here are some tips:

Use the smallest angle possible where the very edge of the blade is visibly in contact with the stone (for maximum structural reinforcement).

Some double hollow ground knives have a mini-bevel that is put in at the factory (i.e. Landwell) which sort of predetermines the knives sharpening angle out of the box. This looks like a small bar along the edge of the blade. Also, the edge of your knife (made by anyone) will bend over time with use. In either of these cases, try this: Place either side of the blade on a stone at an obtuse angle (>45°). Slowly tilt and drag the blade down towards the stone with light downward pressure until the blade slips. The angle right above the point of slippage is the desired angle.

*I use the singular "angle" because I strive for sharpening both sides of the knife at the same angle until I use the sharpening steel. If the knife has been properly sharpened on the stone, the thickness at the edge will be 0 and the steel will push it in either direction at the microscopic level.I also use the exact same motion on the stone for both sides of the knife: I put the blade on the side of the stone closest to my body, push away with pressure, and let up pressure as I pull the knife back toward me. Feel free to experiment with pushing one side of the blade toward you with pressure, and pulling the other side away from you with pressure. I know this works for many reed makers. To me, this process is simple and encourages a burr in a more consistent way than manufacturing one with multiple sharpening angles. I do, however, alternate directions when I use the rods. Since I don't have available fingers to press the blade onto the rod, I cannot create stability on the rod when pulling the front side of the knife away from me. The knife slips too much.

Level 1 (Re-grinding): Put the front side of the blade on a coarse stone, find the desired angle, and make several passes until you can feel a strong, consistent burr along the entire edge of the back side of the knife (see "Feeling the burr"). Then flip the knife over, find the desired angle, and make several passes until the burr turns over to the front side of the knife.

Level 2 (Sharpening): With the same angle as Level 1, make several passes on the front side of the blade as you did in Level 1 but stop when the knife no longer gives feedback on any part of the blade. Then flip the knife over and make several passes until the knife no longer gives feedback. Repeat this process, flipping the knife back and forth until the blade is evenly sharp (see "Testing for even sharpness").

Level 3 (Polishing): Repeat the process described in Level 2 verbatim.

Sharpening Steel: Put the front side of the blade on the steel at an acute angle and make a few passes toward your body. Use the smallest angle possible that still generates feedback. Then turn the knife over onto the back side and make a few passes away from your body. Slowly increase the angle during your passes until you no longer receive feedback. This final step separates the reed knife from any other knife and creates the rake shape at a microscopic level.

left: regular knife

right: reed knife

For reference, with both styles of knives, I typically hit Level 2-3 once a week, and Level 1 every six months. I make 10 reeds a week on average. Unless the gods intervene, which they sometimes do, the rods keep my knives sharp through a typical week of reed making.

I hope you find this method useful when sharpening your reed knives. My primary intention when designing this protocol was to create something that is intuitive and easily reproducible. There is nothing more frustrating than being unable to sharpen a knife when you desperately need a new reed. Lastly, I am very open to feedback (no pun intended) if you believe there are other processes that are more effective than mine.